Do You Have Neck Pain? - Take A Deep Breath, Sailor

I know what you’re thinking; “I’ve been breathing my whole life: I don’t think there’s much to learn”. Au contraire, mon frere. I can state without hesitation that there was much that I learned about breathing while putting together this article. I can also state that my chronic neck pain is virtually gone, and my sleep is much improved.

But if you truly understand how to breathe properly, and you can easily and successfully deal with chronic stress, and you are without neck pain then read no further! You are blessed.

The reason I wrote this article was to offer the sailing community an exercise that I have been using for the last few years to improve my cervical (neck) range of motion and reduce neck pain. It also “chills me out” and I find it especially helpful at the end of a workout. When I finish in approximately 5 minutes, my heart rate and respiratory rate are significantly lower. Every time. What does that have to do with breathing? Everything.

I have found that by slowly moving my neck through the typical range of motion (described below) and combining that with a specific breathing pattern, that I could both improve painless range of motion AND improve mood – even better than when I was meditating regularly.

But, as with all advice, you must first check with your primary care provider, neck specialist, and / or physical therapist. They know your neck limitations and can give you specific, personalized advice.

First things first. Why are sailors so likely to have neck pain and reduced cervical range of motion?

Neck Pain

Posture and Movement: Sailing often involves maintaining awkward positions for extended periods, such as looking up at sails, checking the weather, or bending over deck equipment. These positions can strain the neck muscles.

Vibrations and Impact: Sailboats, especially at high speeds or in choppy waters, subject sailors to constant vibrations and intermittent jarring impacts, which can lead to muscular strain and spinal discomfort.

Physical Exertion: Managing sails, ropes, and steering requires physical strength and can lead to muscle fatigue, including in the neck area.

Environmental Factors: Exposure to elements like sun and wind can cause sailors to tense their neck muscles, leading to pain.

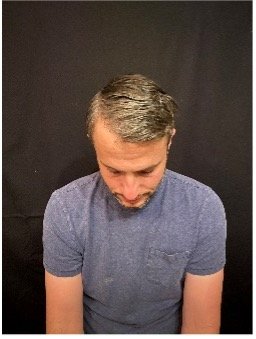

Figure 1: Middle aged sailor looking up

Figure 2: Sailor with neck pain

And like virtually everything else, it worsens with age.

And what about that infernal noise as I move my neck? Well, there are several reasons for it: air bubbles in the neck joints (who knew?), arthritis in those same joints, and stretching and slippage of neck ligaments across the joints. The noise itself is usually inconsequential but occasionally represents a more serious neck problem.

We’ll return to the neck and its range of motion, but first let’s turn our attention to the act of breathing.

Breathing In & Boating – The Connection

Based on rough averages, I have taken approximately 631 million breaths in my lifetime and most of those 631 million were breathed “incorrectly.”

Until my adult years when I started singing and playing a wind instrument, I was breathing like most of you – taking inspiratory breaths by expanding my chest.

“In with the good air, out with the bad”

That was the wrong approach. As all singers know, the only way to fully inflate your lungs is by so-called “diaphragmatic” breathing. As Figure 3 demonstrates, if you want to breathe correctly the first movement should be diaphragmatic. You can feel your “belly” expanding more than your chest.

Figure 3: Diaphragmatic breathing: inhale through the nose, exhale through the mouth. Place one hand on your abdomen and one on your chest. As you inhale, you should feel your abdomen rise but the hand on your chest should not move appreciably. As you exhale through the mouth your hand on your abdomen should fall.

Then, the next phase is the movement of the ribs – kind of up and especially out. And then a third phase (which is sometimes difficult to isolate from the second) is upper lung expansion, easiest to appreciate if you take a deep breath through your mouth. So, while breathing in through the nose, diaphragmatic phase first, then ribs, and finally upper chest phase. That way you fully expand your lungs.

Does it matter whether you breathe in through your nose or mouth? Yes, very much so. When you breathe in through your nose the air is naturally humidified, warmed, and filtered, which is better for your lungs and overall health. In addition, breathing through your nose has several positive effects on brain function. (I’m a neurologist, so humor me).

Olfactory Stimulation: The olfactory receptors in the nasal passages have been linked to improved memory and emotional processing in the brain.

Calm and Focus: Breathing through the nose can also influence the nervous system, promoting a more relaxed state. It can activate the parasympathetic nervous system, which helps with calmness and focus, whereas mouth breathing tends to stimulate the sympathetic nervous system associated with activation and stress responses.

Brainwave Activity: Studies suggest that nasal breathing can influence brainwave activity, particularly promoting a dominance of theta brainwaves, which are associated with relaxation and reduced stress.

Nitric Oxide Production: Nasal breathing increases the levels of nitric oxide, a natural molecule produced in the nasal cavities. Nitric oxide enhances oxygen absorption in the lungs and plays a role in various brain functions, such as neural plasticity, memory, and learning.

Nasal breathing is known to activate the parasympathetic nervous system, which is often referred to as the "rest and digest" system. This activation promotes a state of calm and relaxation in the body, counteracting the effects of stress. The sympathetic nervous system is associated with the "fight or flight" response. Mouth breathing often stimulates this stress-related response. Nasal breathing, in contrast, helps to decrease sympathetic nervous system activity, reducing stress and anxiety levels. Nasal breathing is often a key component in mindfulness and meditation practices. Focusing on the breath through the nose helps in anchoring the mind in the present moment, which is a core aspect of stress reduction techniques.

Breathing Out

If you are living la dolce vita, then you can either exhale through your nose or mouth – it doesn’t matter.

As you’ll see, for our purposes you will need to exhale through the mouth as that is the only way to slow down exhalation. (see Figure 4). And slowing down exhalation also increases the parasympathetic nervous system with its calming “rest and digest” effect on the body. So, by breathing in through the nose and by breathing out slowly through the mouth we can really augment the parasympathetic nervous system “tone.”

Figure 4: Breathe out through pursed lips very slowly. You can use a blowing motion like you are blowing out a candle or place your tongue at the roof of your mouth just above the front teeth and blow – it will sound like air escaping a tire. As you will see, the sound helps to cover up the “snap, crackle, and pop” of your moving cervical spine

Is there any research to back up this pattern? Yes, a recent study from Standford entitled “Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal,” (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100895) studied three respiratory exercises and compared them with an equivalent period of mindfulness meditation over 1 month.

Mindfulness meditation involves bringing attention to the breath to increase awareness of the “present moment.” It does not involve purposefully changing the breathing pattern – a field which is now known by the term “breathwork.” Breathwork includes several different patterns, which involve consciously changing the breathing pattern to affect the brain and nervous system. Many are derived from Yogic practices and one technique, “box breathing” is practiced by the US military.

If you look at Figure 5, the graphic compares Physiologic Sighing (which is what we need to pay attention to), Box Breathing (used by the military for stress regulation and performance improvement), Cyclic Hyperventilation (long inspiration and short exhalation), and Mindfulness Meditation. Physiologic Sighing with long exhalation (twice as long as inspiration) was the best at improving mood and reducing anxiety.

Figure 5: Different patterns of respiration and their effect on lowered respiratory rate and improved mood

So, now you’ve got the breathing pattern – long deep inspiration starting with the diaphragm and finishing with the rib expansion and upper chest expansion. Followed by very slow breathing out through pursed lips as in Figure 4. Think of it this way – when your head is stationary, breathe in; when your head is moving breathe out. It’s that simple. How long for each? Stay tuned.

Neck Range of Motion

We are going to discuss all 6 cardinal neck movements (flexion (chin to chest), extension (head back), head tilting to the right and left, and head rotation to the right and left. In addition, we are going to do head circumrotation, clockwise and counterclockwise (more on this later).

I perform the neck exercises with eyes closed, with my mind concentrating on the angle of my head movement. It’s easy as you only have to think about (roughly) 2 angles: 90 degrees (1/4 of a circle) and 45 degrees (1/8 of a circle or 1/2 of the 1/4 of a circle). (Figures 6 and 7)

Figure 6: 45-degree angle

Figure 7 :90-degree angle

Figure 8: Flexion (head forward); Extension (head back). Each roughly 45 degrees so one long breath for each on the way out and then a long breath for each on the way back. If your head is moving, you should be breathing out.

Figure 9: Lateral head tilt to the left and right. Each roughly 45 degrees Each roughly 45 degrees so one long breath for each on the way out and then a long breath out on the way back.

Figure 10: Left and right rotation. Each roughly 90 degrees so you might try one breath for each 45 degrees; that is 2 breaths for right rotation and 2 breaths for left rotation. And then 1 or 2 breaths on the way back.

These are the classic range of motions of the head. Remember, if your head is moving, you are breathing out. Breath in only when your head is stopped. There is one additional rotation that I have been doing for the past 30 years since attending Philadelphia Phillies Dream Week (See Figure 11):

Flex your head as in Figure 8 and 11, slowly with long out breath.

With head flexed (chin on chest), turn and slowly breathe out as you move your head 90 degrees so that you are looking over your right shoulder. Since it is 90 degrees either one breath or 2.

Then rotate your head 90 degrees until your head has described an arc and you are looking directly above your head at the ceiling. Also, one breath or you can break it up into 2.

Then slowly rotate your head and breathe out until you are looking over your left shoulder.

And finally back down on your chest.

Then repeat steps 1-5 the other way round. Finally, from flexion back up to straight ahead – one breath out.

Figure 11: Neck rotation up and around clockwise and counterclockwise. See text for details.

I tend to break up the 90-degree movements into two 45-degree movements, each with a full inbreath through the nose and outbreath blowing slowly through pursed lips. I don’t time myself, but the out breath is probably 3-4 times as long as the in breath. Whatever feels comfortable. My overall routine takes approximately 5-6 minutes.

Final Thoughts

Like everything else in these blogs, consult your physician, physical therapist, trainer, or other health care provider before attempting this.

If any of the movements are difficult for you don’t do them. It is “permissible” to substitute a second go-round of left and right head rotations or head tilts if you can’t make the big circles.

In fact, just doing breathwork is helpful for mood and anxiety. The neck range of motion exercises helps by providing a structured program and by keeping your mind occupied by paying attention to the angles. And I have found definite improvement in my neck range of motion and reduction in my neck pain overall. And many of us carry a great deal of stress in our neck muscles.

The above exercises are geared towards de-stressing and achieving a relaxed mode – both mental and physical – accomplished by emphasizing the outbreath. If you look above at Figure 5, notice that box-breathing is very different. With box-breathing there is an equal inbreath, hold, outbreath, hold, repeat. Often each segment to a count of 4. It should be apparent why this would be a perfect breathing exercise for the military – they need to be de-stressed (parasympathetic “rest and digest”) but at the same time ready for action (sympathetic “fight or flight”)!

Do these sitting down! You will feel de-stressed for sure. If you do it while standing (especially after some aerobic exercise), you could pass out (I almost did once).

It is interesting that all of us were aware that our emotion and mood (brain) could powerfully affect our breathing – anxiety-induced hyperventilation being a prime example. But who knew that our breathing could have such a powerful effect on our brain?

Finally, the title should really be “Do You Have Neck Pain? - Take A Deep Breath, Sailor, and Blow Out Very Slowly.”